Insights: Am I really disabled?

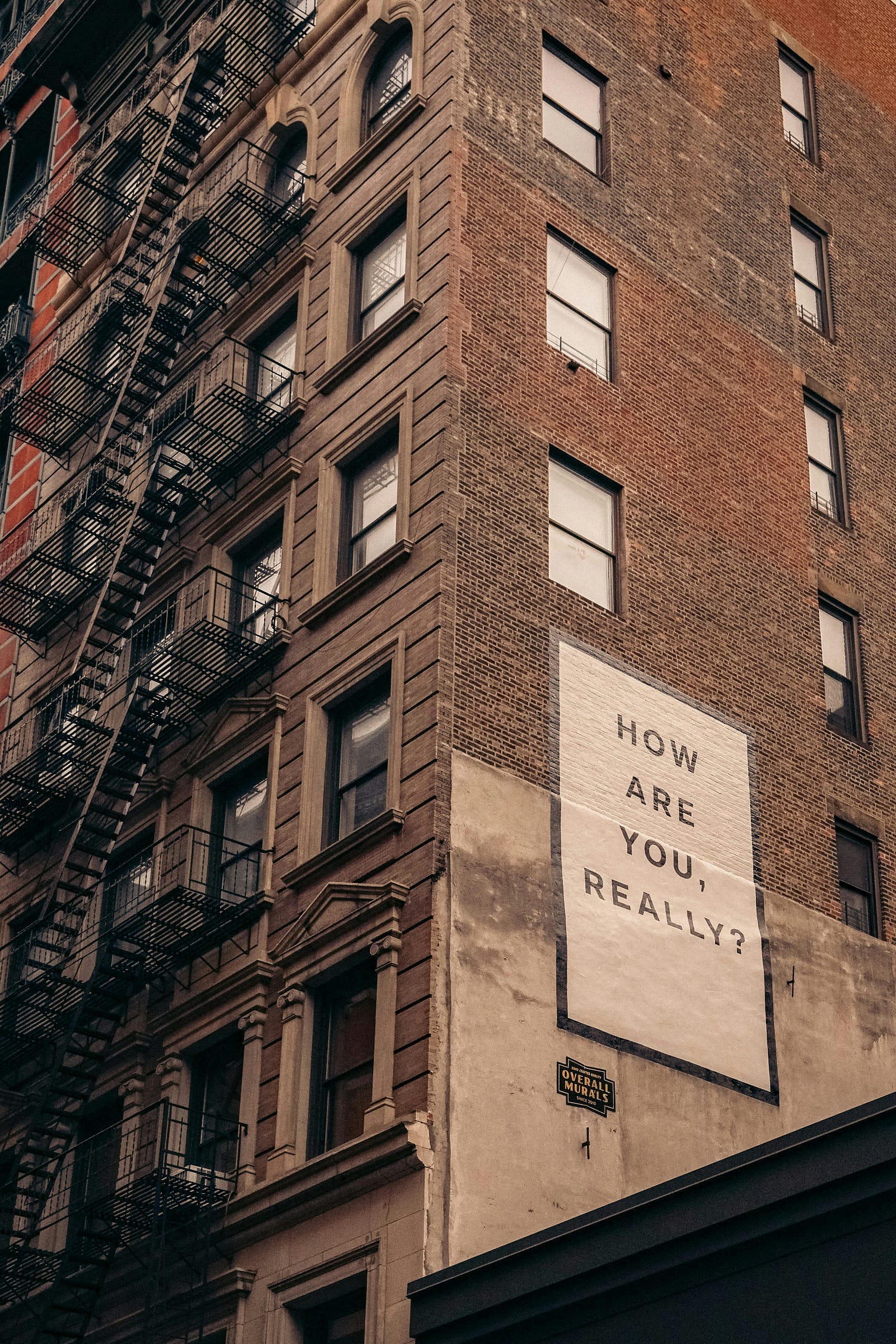

What does having an invisible disability look like? What is it like to feel like you need to 'prove' that you are disabled to your own community?

For several years now, I have had bouts of lows where I struggled to get out of bed; periods when daily living tasks are an ordeal and a general motivation to live is too much to ask for. I have known intimately a tightness in my chest, the overwhelm of panic setting in. Nausea when I am anxious. The urge to say no to events to keep brain fog at bay. Periods when finding words is impossible as my widespread pain is too intense. The reluctance to travel long distances because of the resultant flare ups in pain, fatigue and anxiety.

Despite experiencing emotional distress since childhood and physical pain for the past nine years, I somehow hadn’t thought these would count as disabilities – together or separately. Until one day eight years ago, when I heard A talking about disability and law in a hotel conference room in Delhi. She was a phenomenal facilitator who broke down the diverse categories associated with disabilities such as visual, hearing, physical, neurological and psychosocial disabilities. Her presentation brought a new non-medical perspective to how we need to expand our understanding around what counts as a disability. As she spoke, I silently pondered if what I lived with could be called a disability. A few scenes played in my mind. That time in Grade 5 when I wrote an anonymous note to my school counsellor explaining my distress. Or when I was 20 on a phone call with my sister who lived away from home, crying and asking her if she could tell our parents I was suicidal.

The next day, after I'd spent some time thinking about my experiences, A and I found ourselves sitting on the same side of the breakfast table. I asked her tentatively if there was a difference between mental illnesses and psychosocial disabilities. In reply, she explained to me the term psychosocial disabilities. She said that depression, anxiety, panic attacks, delusions and even dissociation impact how those of us living with mental health conditions experience the world. This, in turn, can lead to challenges in participating, being, growing and learning that are not experienced by others around us. When our mental health gets in the way of our social experiences, it is termed a psychosocial disability. Our conversation, that presentation, her response, all left me asking: did I live with a disability because of my mental health conditions?

***

I had already been working with the disability community for a few years by then and for the most part, I saw disability as both visible (blindness, locomotor disabilities, wheelchair users, crutch users) and invisible (autistic folks, those living with schizophrenia, bipolar, epilepsy and so on). But what about me? I am able to participate in activities without revealing too much about how I am feeling. I can do this with the support of my medicines, deep breaths when the anxiety gets too much, frequent breaks to support the pain, and with quiet, internal reminders of the bed with a weighted blanket and many hot and ice packs waiting for me at home. So to anyone not seeing me at home or in the midst of a flare of all my symptoms, it isn’t immediately evident what I am feeling.

Coupled with this, I struggle to explain how I don’t feel the same one day to the next. On some days my pain, anxiety and low moods are in control, and I just need to rest and get a good night’s sleep. On other days, the pain makes finding words difficult, and anxiety makes me relive every sentence I’ve spoken, ranging from five minutes to two years ago. It is possible for me to eat in a standing buffet on some days with limited repercussions afterwards. Sometimes, the consequences are not being able to leave my bed for 48 hours or, at the least, needing to sleep for 14 hours straight. At other times, it means several months of trying to restore my energy and calm.

This kind of variance in my capacity requires me to share how I am feeling very vocally in order to both explain why I am behaving the way I am, or while asking for support — a place to sit down and eat, perhaps. My discomfort in having to draw attention to my needs – to make visible something invisible – forces me to power through and deal with the consequences later.

Not being able to always vocalise my experiences has meant that most people find my experiences impossible to understand – that is if they believe I am experiencing them in the first place. They often ask me questions and make comments based only on what they see. "But you look fine!" "Someone who is depressed and anxious can't work like you do." "You are always smiling, what problems could you have?"

In her piece ‘On Being Ill’, Virginia Woolf wrote about the “daily drama of the body” of which there is no record, highlighting the mystery and the great wars that the body wages “in the solitude of the bedroom against the assault of fever or the oncom(ing) of melancholia”. My friend Priyangee, who is a lawyer and autistic self-advocate, shared with me her interpretation of the idea of a 'high functioning’ autistic person. She said, “If we seem high functioning in one area, it often comes at the cost of ‘functioning’ in other areas. My high functioning at work comes at the cost of being messy at home. I cannot manage both, physically and mentally.”

Both Virginia Woolf and Priyangee tap into the same idea. That the whole picture is not visible to everyone. We can’t ever know what happens inside someone’s body and mind, or even hope to deduce it from what we can see. This rings true for me: I spend a lot of my time in my house recovering from my day-to-day tasks. But these long periods of recovery aren’t visible to others — unless I choose to make them so.

***

During the peak of the coronavirus second wave in India, while working on urgent Covid-19 relief, I met K, who is also disabled and chronically ill. Our experiences were similar in many ways - we both lived with inexplicable pain, unprecedented lows and anxiety spirals. We both worked in the disability community. We both struggled to be accepted as disabled. Our disabilities were for the most part ‘invisible’ – unless we disclosed them in convincing, detailed ways. Consistently.

Over the years now, our chat on Signal has become a place for us to explore this invisibility. Especially why we in the disability community continue to see disability through the lens of its visible markers. What makes people doubt the validity of our experiences? Is our disability really invisible or is it being invisibilised? Is vocalising our distress and pain the only way to find community and be accepted?

I once wrote to K after a long day at an international event about the questions many disabled folks asked me. “What disability do you have?” “We didn’t know you were also disabled.” Each time I revealed my disabilities, the person responded with shock and disbelief. This persistent disbelief is hard to shake off. Especially when the scepticism of whether I'm disabled or not follows me into my work with the disabled community. You can be lying on the floor of the conference room in mental and physical exhaustion or candidly share how flickering lights and loud sounds can trigger a migraine - but questions about the ‘realness’ of your disability still follow you around.

This doubt wriggles its way inside my mind and forces me to cast doubt on my own experiences. I begin to scrutinise my good days and bad days through this lens: if I can walk the length of this large airport, maybe I don’t live with chronic pain. Is my anxiety that bad, if I am able to manage a day at my computer despite it? These doubts make me place the burden of proof on myself (and others like me who are struggling) and supports the idea of a ‘real disability’ vs faking it. It nourishes the ableist idea that everyone is non disabled - unless a visible marker exists. It argues that there is more value in being productive than the costs of productivity on the body. It makes me succumb to a hierarchy of which experiences are valid and whose needs deserve priority. I often catch myself wondering, “Am I really disabled?”

That the seeds of this doubt are being sowed by the very community that is meant to understand, to have my back, makes it harder to digest. Or worse, makes me trust their voices of dissonance over my own experiences of distress.

Is my difficulty in vocalising my experiences part of my own internalised ableism? Perhaps. But it also seems to be a way of not grappling with the reality that even when we show ourselves (like I have done so many times in the past), people still choose not to see. In a way, I can almost understand, because I sometimes struggle to see myself as disabled too.

K said to me once during a rambling complaint about the erasure of our disabilities, “There is always going to be someone to whom we are not visible, but sometimes we have to make the choice — to whom we show ourselves.” Because not everyone is ready to see us. So, during conferences and events when people ask me if I am “really disabled”, I try to remember that they can’t see how I am feeling. Instead, I message K or another friend who can hold space for me, who can help me feel less anxious or provide the emotional support I need.

Being each other's witnesses in a wider world that already discards the disabled experience as ‘too much’, and where many people have strong ideas of what disability looks like, is vital and healing for us. I still hope that as a community we can build better worlds. Worlds where we focus on learning from each other to grow and diversify our understanding of disabilities, the people who experience them, and how they manifest differently for each of us. Where, as Ada Limón writes,

“I could be both an I

and the world. The great eye

of the world is both gaze

and gloss. To be swallowed

by being seen. A dream.

To be made whole

by being not a witness,

but witnessed.”

I have never felt so seen in a long time... The daily struggle of questioning yourself, your reality, and everything....

this piece has been such a comfort to me this week, because it reminded me that, yes i'm not alone but also that i can lean on my loved ones when i feel similarly (or Not feel at all ha...ha...). thank you so much for writing and sharing it with us <3